Employee Net Promoter Score (eNPS) is the HR edition of the customer satisfaction metric that became famous for the masses through an HBR article in 2003. In other words, it’s been around for a while. Looking at different vendors' offerings and listening to HR professionals, eNPS is used to measure engagement, take the pulse of the organization, and in some cases to follow up on the brand perception. So, what's the problem with eNPS?

Everyone is using it, shouldn’t that be an argument for that it's kind of OK? Well, not that long ago, it was OK with corporal punishment of children or to use unlimited amounts of DDT against insects. A lot of people did that. Still, that does not per se indicate that it’s a good decision.

Below, I’ll shed some light on the most problematic implications with eNPS.

- NPS itself is a problematic method

- HR miss out on the primary wins

- The question does not measure what we want it to

- The scale is problematic

- The analysis method is worthless

- It’s unpedagogical

Do you want to know more about how to use surveys within HR?

NPS itself is a problematic method

The NPS methodology is not a success story, there’s actually a lot of relevant criticism. In short, it does not perform better than other similar metrics. Add to that, that it might not be applicable across respondent segments, since the likelihood to refer something is not consistent over age spans and that there are a number of implications with the calculations (we'll come to that later). What NPS wants to achieve is too complex for “just one question”, research shows that a multidimensional approach is preferred. That gives us few reasons to look at the NPS methodology for a start.

HR miss out on the primary wins

There is one clear advantage of the NPS methodology. It’s not a research method, but an operational model - and one embedded in the business. In other words, it's not just a way to ask things but also to continuously follow up on the replies and make business improvements.

The idea within NPS for consumer research is that a customer gets a survey connected to their purchase. The result from that survey then goes into two feedback loops. The first loop aggregates insights on a high level to make strategic business decisions for the future. Basically, it's the classic way to follow up on a survey.

The second loop is more interesting. It’s the immediate feedback loop back to the shop where you bought your product. The shop manager gets feedback after each purchase. Based on that, the manager should make sure to continuously improve the shopping experience for all customers. If a customer is dissatisfied, the shop manager is supposed to take action on it. The manager should sort it out with the customer and also look at the structures that made the mistake possible in order to avoid it happening again.

The first (strategic) loop is fully possible to replicate for HR. But how do you apply the second loop in a work context? “Hi, I’m calling from HR, we saw that you gave a meager score in our last EE survey. What can we do for you?”. Wouldn't think so.

eNPS does not measure job engagement

What does it mean when we ask the following:

How likely is it that you would recommend your employer to a friend or an acquaintance?

How good the question itself is, naturally depends on what we use it for. Most often, it’s used to pulse organizational engagement (which is an additional problem with the eNPS), which leaves us with two questions:

- Does it measure engagement?

Going back to research, I have so far not read one published peer-reviewed scientific paper saying that eNPS is a valid measure for engagement (or related work performance) that also is better or at least equal to other options. - Is it reasonable to measure engagement (or brand) with only one question?

In short, using a single item is less reliable than composite scores (indexes based on a number of questions). Depending on what exactly you want to measure, it won’t even be possible. For example, you cannot measure engagement with less than three questions when using the established and reliable UWES method.

Add to above that even though we could measure it with one question, this specific phrasing might not be relevant. People don’t care that much about the company, as about the team - which is the more important segment when measuring engagement. There is generally a larger team engagement spread within companies than between them (more about this in Nine lies about work). In that case, why do we ask if someone would recommend the company?

eNPS might not even measure brand

As stated earlier, eNPS might also measure your employer brand. Basically how many would like to recommend your company as an employer - but does the question even measure that? And why would the inconsistency in the recommendation rates from consumer NPS not follow eNPS?

A basic criterion for measuring something is that the item (question) you use shall give you an answer directly connected to the question and not be too open to other interpretations. After analyzing responses from a number of different organizations on that specific question, it is clear that there are gaps in the validity of the phrasing.

"Would you recommend a friend to work here?" does not only give you an answer to if you’re a hot employer or not. It also gives answers such as “I wouldn’t want to work at the same company as my friend”, “My friend is within another business and could not be employed here” or “I would recommend applying for a job here, but not in my team/department/(etc)”. And those responses don’t just show up once in a while, they are in opposite quite common.

Still, the "recommend" question might be one of the better options if the brand actually is what you want to measure. However, you should avoid to do it with the NPS scale.

There are better options than 0-10

The eleven-point scale is unique for the eNPS, but there is one huge problem. There is no evidence that it is better than other options, rather the opposite. When you design a scale you want it to give you good a distribution, meaning that you want as nuanced answers as possible (not just “good” or “bad”). At the same time, you as a respondent need to be able to distinguish between the options - what is really the difference between 2 and 3, for example. In addition, respondents need to be able to be consistent, both across each time they respond and across the population. This is especially important since there are clear cuts in how the NPS score is calculated. If you’re not crystal clear on the difference between a 6 and a 7, you will make the NPS score vary between -100 and 0.

There are better options. Both in marketing and psychometric tests, a seven-point scale provides spread without watering down the meaning. You can also label the options, to make it clear for the respondent what a 5 out of 7 really means.

eNPS analysis is full with problems

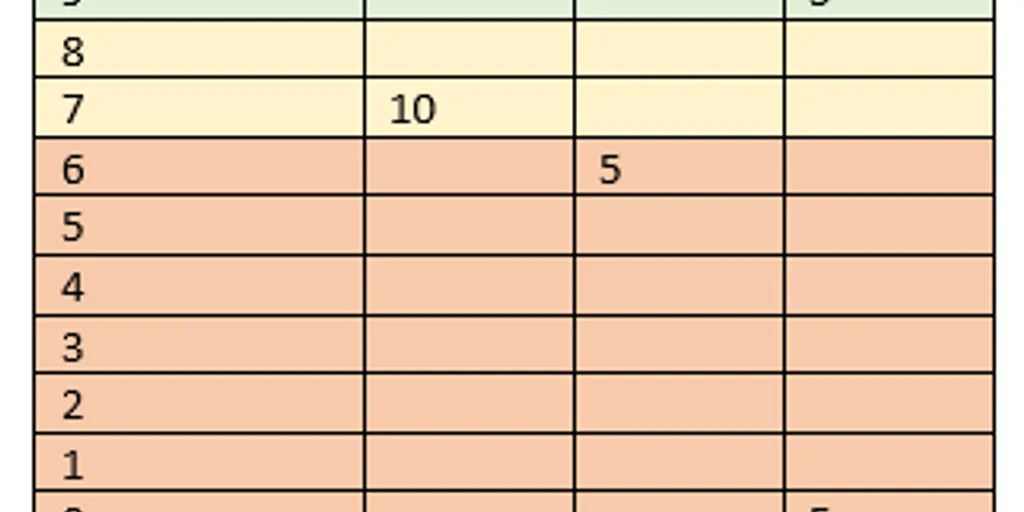

The challenge does not stop with the data collection, it follows in the analysis phase where there are a number of implications. The largest problem is that the score is more or less useless in describing differences in distributions. This complicates it when you want to follow a trend over time or compare different groups. You can get quite different response distributions, but they end up in similar eNPS scores anyway - or the other way around. This means that you might miss out on real improvements or declines in the score.

The three different teams above have the same eNPS score, which is a problem since their answers are completely different. Comparing the eNPS score with an average score shows how different views we are presented with. The response distribution for the three teams above will most likely have three totally different actions that need to be taken to further improve their work environment.

In addition, there are other statistical implications such as large ups and downs compared to average scores and challenges regarding samples.

It’s unpedagogic

Last but not least, people say it’s easy to understand… but really? What makes the most sense: “on average you got 3.5 out of 5” or “22 % answered 9 or 10, and 65 % answered below 6. Therefore the NPS score is -43 - and that on a scale from -100 to 100."

Summary

To summarize, you can use NPS in HR, but there is no evidence that it works. Using eNPS for the engagement problem is kind of like treating the flu with cheese. On top of that, there are challenges with both the data collection (the phrasing of the question and the scale) as well as the analysis (samples, distributions, and volatile trends). And not to forget, you cannot apply the continuous improvement method to HR practices. Thereby we switch the operating model back to only become a flawed research model.

Now you might ask yourself if this only applies to eNPS or if also your candidate satisfaction survey (cNPS) is at risk. As you understand, the statistical challenges are still there, and I haven’t seen any scientific research on that specific topic either. That leaves us to that the question itself might work but on the other hand… If you’re interested in if a candidate was satisfied, why not ask just that instead?

Want to talk more about how to measure People processes?

If you liked this article about eNPS, you should check out Why a pulse survey won't solve your problem.